About time: Dárida Rodrigues

To continue our discussion about time, we spoke with artist Dárida Rodrigues, originally from São Paulo. Her research materializes through audiovisual installations, audio walks, performances and site specifics as an attempt to investigate relational art and human consciousness itself. Dárida shared with us the experience of creating in isolation, the role of plenty of time in artistic practice and her personal relationship with the passage of time.

I would like to start by talking about the intentionality behind your work on “lengthening time” for a closer look at our surroundings and what lives inside us as well. Where did this need to unite artistic practice with meditative methods come from?

D: Well, I feel that time, or rather the passing of time, is one of the only constants in our experience, while everything changes. And the possibility that time “stops, stretches or flies” based on our perception of each particular experience has always interested me a lot. I think this phenomenon of change in perception and, above all, the relationship established between it and our mental and emotional states, is also one of the things that have always connected me to meditative practices for a long time now.

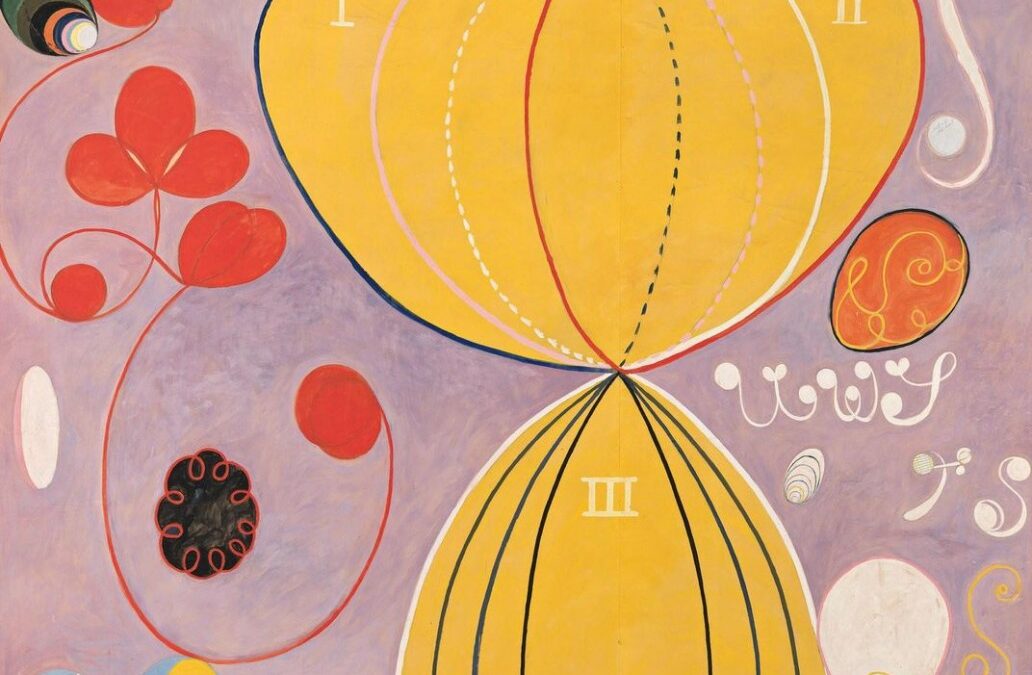

So I think that this opening of an internal space where temporality unfolds in other possible configurations and that simultaneously allows one to more fully inhabit the present moment, which I explored a lot through meditation, of emptying even for a few seconds the mind also crosses my work, I think, before intentionality. It is really a gap that attracts me as an investigation and that I am interested in exploring in this transposition of territories between art and life, perhaps because, at least for me, these meditative fields, or the spiritual, if you like, is also the field where art operates . It has become naturally part of the process to integrate or even subvert meditative methods when trying to create relationships between subjectivity, time and space.

His last work “Vice-Versa” explores this idea of movement of affections that interconnect the inside and the outside, the reception and expression of information and images… And the work also ended up illustrating the passage of time through the observation of the flow of people on the street and interactions with the work itself. What did you glean from the experience of creating the work “Vice-Versa”?

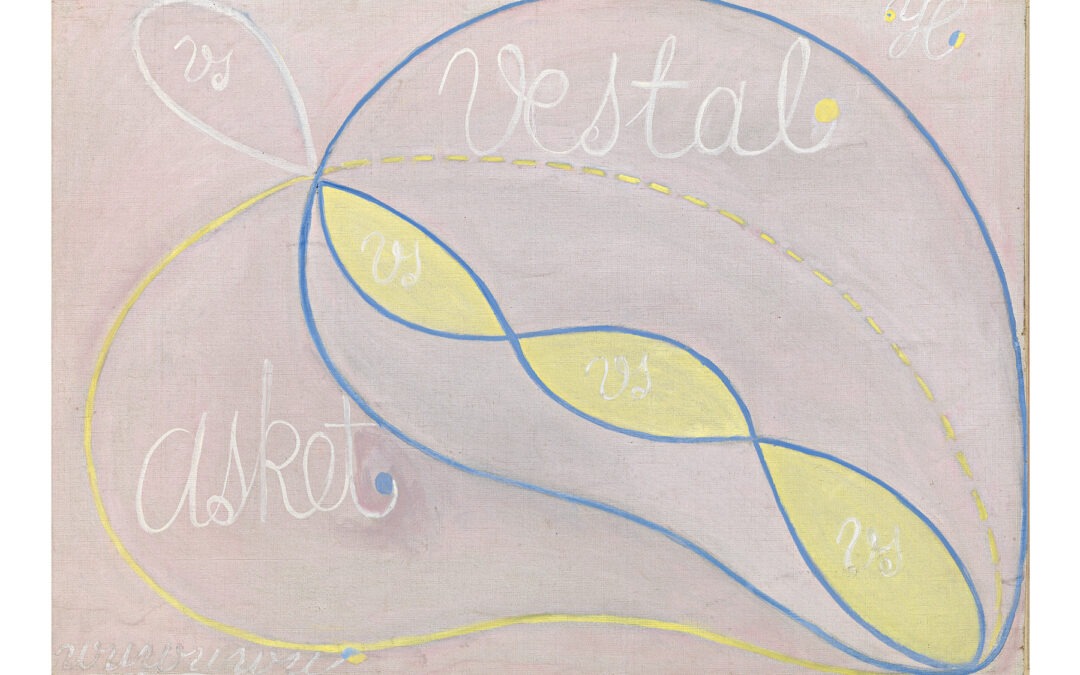

D: I'm still processing this crop…because the work has uncovered many layers that have been interesting to observe. But I can say that this impulse to try an inversion of point of view, taking advantage of this relationship between the inside and the outside that the space of the shop window and the street provides, through the resource of projected video, allows many other relationships to be established and developed. confront, as for example that of time with space, in the inverted mirror that does not directly reflect the observer, created through the video and that draws our attention a lot for the possibility of experiencing 2 or more temporalities simultaneously, such as what happened inside, what was going on outside, in the present moment and what was going on in what was seen in action in the video performance/projected mirror, which still brought other speeds, repetitions and interventions and which mediated these different relationships between subjects, plants, passers-by of the present and the image. I feel it's worth exploring this relational timespace further.

His other work [Des]segredo proposed a trajectory of a mapped path to traverse the work in a certain space. How do site-specific works manipulate our perception of time?

D: In the process of creating [Des]segredo, which was also a master's project, the audio-wall À Luz, developed for a specific journey in the Lisbon Fine Arts building, which is a very old building, of historical materiality, where one feels the weight not only material but temporal as well; it was interesting to explore the proposition of an inner (or meditative) drift through displacement in space, as a process of approximation to a common place of a one-to-one relationship, around the idea of the Secret, which was proposed at the end.

From this soundscape brought by the voice instructions, experienced and recreated in the present when walking through space and also through the subjective temporalities that happen at the moment, for each participant, I was also able to observe how a space/time journey was made specifically to exist in a space in an artistic scope, can not only influence (or manipulate) our perception of time but also be influenced by it. This is because I feel that the site-specific works are intrinsically linked to the space, at the same time that they open up, through this possibility of the manifestation of a subverted temporal space, to interventions and transformations of the same and in this sense, they are very interesting in this exploration of the interior and relational universe in dialogue with temporality.

The work [In]surge, which was created during the quarantine, is another work of auditory immersion. One of our questions within the theme of time is to investigate how the lack or abundance of time affects the creation processes. What was it like creating this work during a period of isolation?

D: It was, at the very least, a good questioning exercise, so much so that in the beginning I called the [In]Surge series “Exercises for “Touching the becoming, Embracing the pain and Chewing the real”.

I, who had decided to kind of transgress in the field of art, some meditative methods, by proposing displacement, distraction, a poetics that involved me personally in the texts and in the audios, suddenly I felt that life asked, first of all, to digest, with an unprecedented limitation of space and movement, a dystopian and uncertain reality, where these “conventional” meditation methods, despite being very useful physiologically, did not seem to make much sense to me at that moment. It was really a necessity to integrate them with the creation process. So I started to write these audio instructions to work with the possibilities of a meditative and sensorial abstraction from this condition of confinement and the sudden pseudo-abundance of time and impossibility of movement, with all the emotions and questions that arose and insurged internally.

Is it possible for artists to take advantage of the esoteric nature of the creation process in an extremely fast-paced world like the one we live in today?

D: Yes, it is difficult to think what is not possible in terms of art. But personally, I feel that it is essential to let ourselves exist in life and art in the most integral way that is possible for each one, so as not to be totally swallowed or captured by the extremely capitalized and mediatized life, which characterizes the instituted, flawed, “humanism”. but accelerated today. And I think that this esoteric, spiritual or transpersonal universe is much broader and present in our subjective experience than we often imagine or intellectualize, especially since we almost always operate within the hegemonic Western thought, where we have difficulty making room for what is not it can be configured by these parameters and so we do not connect with the possibilities of intuiting and creating rituals or spells that are natural and not “supernatural”, to explore our inner universe and invent other realities. The artistic field is very fertile ground for this exploration, in my opinion. Much of what we see as part of an esoteric nature and that is not related to the rational thinking we know, may be common practice for some other communities and species, for example. If we see or make art only from the point of view of our (often limited) culture, we will always leave out experiences and experiences that may be fundamental to exist and who knows, to flourish in fact and politically in the present. I don't see space/time more receptive to this than art.