by Stephanie Wruck | Apr 30, 2021 | Article

Eduardo Politzer is a Brazilian sound designer and artist from Rio de Janeiro and today we talk to him about his digital work “Labirinto”.

This is an invitation to put your headphones on, get lost, rediscover yourself and, hopefully, dream. Politzer created a new digital space full of sounds, memories, dreams, poems and loose thoughts. As you navigate the labyrinth, clicking on hyperlinks that redirect you to different corners, you draw your own path. Sometimes the labyrinth can be deeply moving and personal, at other times it can be relaxing and fun.

We had the opportunity to navigate Eduardo's labyrinth with him, asking questions along the way. He shared with us how the process of creating the work was and what he learned from the experience.

“Put on your headphones.

Get lost, dream.

When you realize you're in a labyrinth

it's because you've been there for a long time.

But don't rush,

Perhaps you will learn something along the way.

Maybe you'll find something valuable,

Maybe you will learn something valuable about yourself,

Perhaps,

Maybe you'll wake up with a feeling,

Perhaps your brain uses this time to simulate different situations.

To discard what is of little importance.

To prepare for something in the future.

In this labyrinth you will find characters and places,

Sound and image.

Time and thought.

Metaphysics and nonsense.

I'll tell you my dreams

And then you tell me yours.

This is an ornament

A necklace that we place around the neck of time,

To see if it gets tamed.”

We invite you to explore the labyrinth on your own, visit here. Click here to visit Eduardo's website. Follow him on IG: @eduardopolitzer

by Stephanie Wruck | Apr 26, 2021 | Article

In the last year, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unquestionable protagonism of work in digital environments. Like other productive sectors, artistic making underwent several adaptations during this period. We at Coletivo Amarelo have proposed in the last two weeks a historical investigation of the relationship between art and the Internet, suggesting reflections related to the first experiments with technology and the interventions of the NetArt movement in the 90s, often predictive of the performance of artists in an increasingly digitized world. . The previous texts are available on our blog under the tag “Internet”. Click here to read our last post about the Net.Art movement.

In the first months of 2021, we witnessed what seemed to be the trigger for a new era in the relationship between art and the internet. NFT editions invaded social networks and art groups shortly after the traditional house of Christie's auctioned a fully digital work of art for US$ 69 million (or R$ 382 million).

“Everydays: the first 5000 days“, by contemporary digital artist Beeple, fetched US$ 69 million at the latest Christie's Auction House auction.

The work is a collage of daily illustrations that the artist made over 5000 consecutive days (Image: Beeple/Christies available on BBC.com)

What happened? Where did it come from? Is this a new trend?

After nearly two decades of unstable speculation, cryptocurrency wallets such as Bitcoin have especially soared in the past year. The value of just 1 Bitcoin jumped from US$ 0.34 in mid-2010 to around US$ 50,000 (or approximately R$ 280,000 – Google quote: Morningstar and Coinbase, query 4/23/2021).

However, not every type of product had the same possibility of being introduced in the cryptocurrency market, because the monetary commerce that takes place in the technological world started to demand a safer structure, since the entire transaction is carried out in a currency that does not exist in the the real world. The Blockchain online system was created from this need. It is a platform that functions as a cryptocurrency exchange and serves to explore, track, monitor and record complex transactions.

In Blockchain, each trade is encoded as an immutable link, and therefore other objects that would need non-exchangeable value in more secure transactions have now been introduced into cryptocurrency trading, such as works of art.

But what does “objects with non-interchangeable values” mean? Imagine two situations:

- You are in a store and your purchase totaled $ 100. You have the option to pay using two $ 50 bills, 5 $ 20 bills or 10 $ 10 bills, etc. Therefore, common currency is mutually interchangeable (or fungible).

- Let's say you own three houses located on the same street, one worth $ 500,000 and two others worth $ 250,000 each. Although their price is close, if hypothetically the two houses worth $ 250,000 are grouped together, they will not necessarily have the same stipulated value as the house worth $ 500,000, even though the combined unit values result in an equivalent value. This is because each house is unique and has its own characteristics, that is, they have values mutually non-interchangeable (or non-fungible).

In this sense, Blockchain allows objects with non-exchangeable value to be traded for cryptocurrency, maintaining a fundamental aspect: uniqueness. For this, each object will be linked to an immutable link recorded in the Blockchain. These immutable links are called NFT (Non-fungible Token). The NFTs are also able to sustain another essential aspect for the art market: the concept of scarcity, responsible for valuing the piece taking into account how many identical units exist or not. In addition, NFTs offer a new type of registration for artists, since the immutable links registered on the Blockchain can contain all the information and technical specifications of the work produced in a “Smart Contract” format.

In short, the new revolution in the world and in the art market allows works to be sold 100% digitally, forming a new segment: Crypto Art. Each image, video, sound, text or software file, even if it is unique or limited edition, becomes an NFT registered on the Blockchain. As a result, each NFT will be priced and sold in Cryptocurrency.

Still from the NFT video work of American graphic designer Kii Arens based on a real house in California.

Bidders will bid on this NFT, with the winner also receiving physical property at 221 Dryden Street.

After this process, the NFT has a traceable contract with the most credible, safe and innovative copyright. For example, until the emergence of Crypto Art, an artist did not receive a percentage of the profit corresponding to the resale of his work. With the Smart Contract, a clause can link a mandatory percentage of transfer to the author of the work in case the NFT is resold. Noah David, specialist responsible for the first NFT auction held at Christie's, declared that “the potential imposed by NFTs to break with the traditional model of art auctions is immense”.

Still, they are still digital files, so can anyone have them? In theory yes, in practice no, because only those who have the NFT own the work. The rightful owner will be insured in the Blockchain registry.

It is worth remembering that Crypto Art is highly influenced by video games (by the way, a visual design niche that recently gained the well-deserved position of production with artistic content). In other words, the featured look has futuristic features that even hark back to NetArt's predictive interventions.

“Gods in Hi-Res”, by Canadian artist Grimes. The work has a futuristic look inspired by games.

The NFT was auctioned for $ 77,000 (Image: Grimes/Niftygateway)

Finally, it is in this context of congruence exercised by a technological environment of infinite possibilities associated with a global situation of digital protagonism, that a new era for art and the internet is installed. Crypto Art proposes a reintegration of the avant-garde of the 90s. A reboot. It is up to us, artists, to reflect on our own conservatism in relation to advances in art with technology. Crypto Art establishes itself not just as a trend, but as a movement. It is naive to believe in the illegitimacy of the movement based solely on the fact that this art “does not exist” in real life. After all, if digital exists, it is because we created it, making it part of our reality. With this, art fulfills its role as a catalyst for new readings of these realities.

REFERENCES:

Extraordinary Sale – BBC News Brazil

JPG File Sells For 69 Million – New York Times

NFT Artwork Being Sold With Physical House In California – Dezeen

by Stephanie Wruck | Apr 15, 2021 | Article

Net.Art emerged in the early 1990s, when a group of artists began to explore the possibilities offered by the internet: from promoting their work to using software and browsers to to create new works. These artists quickly realized the importance of the internet as a tool to rediscover the intrinsic value of art, disconnected from the mechanisms of the art market, shifting the focus from the object to the process.

The works carried out during this period illustrate the dynamic and collaborative spirit of the internet within the creative process. The internet was a new territory in which artists could explore possibilities for novelty that existed beyond physical spaces. This total freedom of intermediaries placed by art institutions on the artist's work and the versatility of the internet as a medium, transformed the net.art movement into a revolution. It challenged the way art was made, exchanged, promoted and displayed.

THE ARTISTS

We've gathered three notable artists linked to the net.art movement, highlighting the importance of their work.

Olia Lialina

A pioneer in the net.art movement, Lialina is best known for her 1996 browser artwork “My Boyfriend Came Back From The War”. can navigate by clicking on different parts of the screen while a narrative is developed. The story is about a couple who are reunited after the war and their difficulty in emotionally reconnecting. She confesses an affair with the neighbor while a marriage proposal comes up. This cinematic, grainy, GIF-like piece influenced many later artists who experimented with browsers and software. visit the work here.

Mouchette

Mouchette is the work first laid down in 1996 by Amsterdam-based artist Martine Neddam. She invites the viewer to navigate through a labyrinth of HTML websites of the turbulent life of a teenager struggling with suicide and trauma. The play is dark but humorous and fun, keeping us guessing what might happen next. At the time the work was created, users found instructions on where to find it through an interactive bot, quizzes and email. Public participation was a central part of the work, creating a space where we could all be a part of. Users were also able to submit their own net art works via Mouchette's website. visit the work here.

Alexei Shulgin

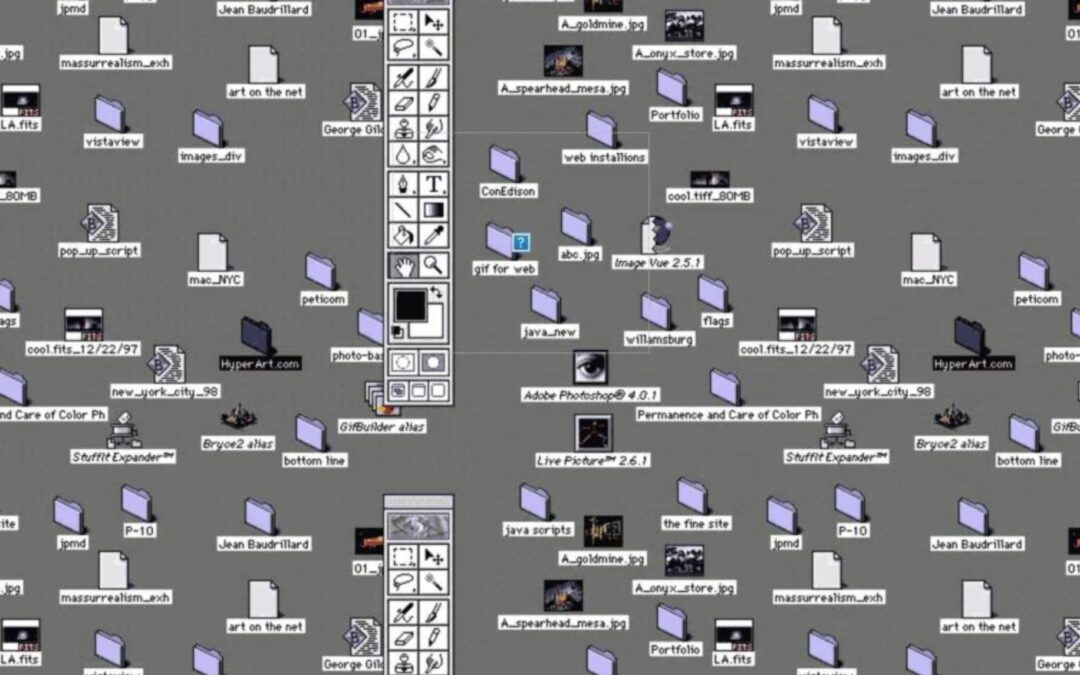

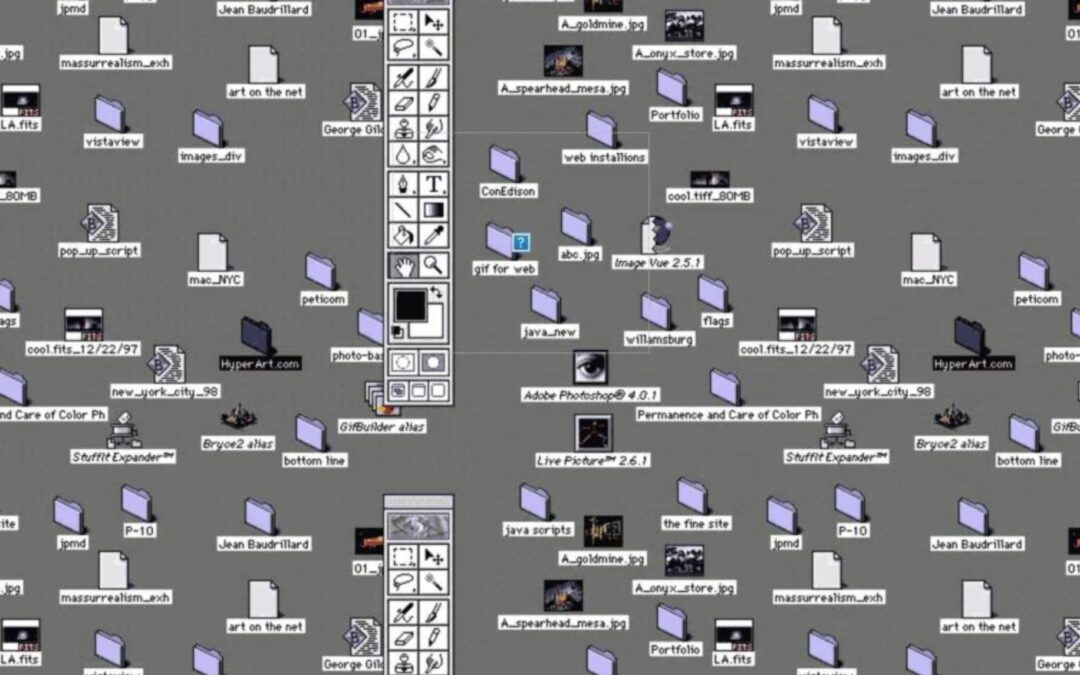

Shulgin's 1997 “Form Art” is another important archive of the net.art era. He used HTML buttons and boxes to create monochrome compositions that served as a study in the mechanics of HTML itself. However, “Form Art” became a more lyrical and abstract work of art, exposing the skeleton of the internet in a way never seen before. Shulgin said: "Bringing them into focus was a statement of the fact that a computer is not an invisible 'transparent' layer to be taken for granted, but something that defines the way we are forced to work and even think." visit the work here.

During that time, net.art artists were able to design a new emotional universe, existing alongside the physical emotional spaces we inhabit, eventually becoming the digital infrastructure we navigate today. The hybrid nature of the internet, where all art forms have a place to live side by side – images, text, video, sound, etc – impacted the core of the creation process. There was no longer a separation between where you create, collaborate, design and promote; everything happened on the internet. The idea that the internet could accommodate all aspects of the creative process influenced both the works themselves and the public's response to them.

“desktop is“, Alexei Shulgin, 1997

Josephine Bosma, critic and theorist specializing in art in the context of the internet said:

“To put net.art in the right perspective, art history must be partially rewritten. Much emphasis was placed on the commodity status of works of art during this century. Inevitably, this trend has excluded certain arts and artists who do not meet related criteria. Perhaps net.art offers us the opportunity to rethink the criteria by which art is valued. Of course, net.art is not an easily noticeable object. Much art on the internet appears very dispersed due to the use of multiple media and transience. To experience it, one must be an avid follower of net.culture.”

Bosma's vision of the impact of the quality of the internet space on the arts is still incredibly valuable today. What she called net.culture in 1998 resonates with all of us – artists and consumers of art – perhaps more than ever. As we weave through this thick blanket of media across social platforms and the web as a whole, it's inevitable that we'll wonder where we're going next. Perhaps we should follow Bosma's advice and rewrite art history.

How do we categorize art in the context of the internet? Is there still a need to categorize different forms of art? Net.art has made it almost irrelevant to distinguish what is art and what is not. Therefore, Bosma concluded that artists who do not wish to describe their work as art can avoid limiting discussions about the relevance and value of their work within an “art market”. As many net.art artists preferred to remain invisible, dissolving in their ephemeral and temporary works on the internet, Bosma left us with an important reflection: after all, does art only profit from this obscurity?

“Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century“, VNS Matrix, 1991

“brandon“, Shu Lea Cheang, 1998

“mobile image“, Kit Galloway, Sherrie Rabinowitz and collaborators, 1975

“summer“, Olia Lialina, 2013

A lot has changed since 1998, but the internet remains a place where walls are constantly being knocked down and built again. New visual languages are written every day, adding fuel to our dizzying shared digital experience, revealing more about ourselves through edited and impermanent layers. How can art help us understand the ever-changing mechanisms of creative expression?

After all, is the internet our greatest ally when it comes to making art?

References: